Project Summary

Climate change will have a significant impact on global population movement, with the potential for as many as 1 billion people to be displaced by 2050 (Henley, 2020). The World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) is the global voice for occupational therapy and sets the standard for its practice (WFOT, n.d), and is developing online learning programs for OTs to work with displaced persons. Currently there is one program being offered, which has been developed by the e-Learning organisation Reality Learning (RL). Having identified the demand for further learning programs in this space, RL is looking to develop a prototype called Resettling Climate Migrants (RCM) with a view to adding this on to the existing curriculum.

The initial proposal is to work toward creating a wholly online micro-credential that allows learners to engage with the challenges faced by displaced ‘climate migrants’; building knowledge around the impacts that this will have on these individuals and exploring practical strategies to help them settle into life in a new country. The learning outcomes will take into account factors such as place within community and urban planning for future diaspora, with a view to helping survivors build meaningful lives.

The current scope of this project is to create one module to add onto the existing Working With Displaced Persons program. The expected learning time is only 4-6 hours, recognising that learners are busy people and have limited time (Goodyear, 2005, p. 91). This will be made up of core content authored in Articulate Rise, as well as a Mozilla Hubs virtual 3D environment whereby learners will ‘walk in the shoes’ of a climate migrant, and be delivered through WFOT’s Moodle LMS. The content required includes:

- 3 case studies of people displaced by climate change, climate migrant identities (CMI),

- ‘Settling in’ set list from The Middle of Everywhere by Mary Pipher

- WHO social determinants of health framework

- a 3D environment created using Mozilla Spoke to be used in Hubs

There will be no instructor present in the course, which creates challenges and possible risks around the quality of engagement, assessment and feedback. As such, the learning materials listed above have been selected to maximise the quality of student learning outcomes (Meyers et al., 2009).

This RCM module will be designed as professional development for practicing OTs, many of whom will be under 35 years old and have at least reasonable technical competency. Learners may be situated anywhere in the world, so while much of the content will be worked through individually by learners, there will be a strong emphasis on sharing ideas and working toward building a ‘community of practice’ (Wenger, 2011, p. 1) for working with displaced persons. This will not only be valuable for learners, but also aligns with WFOT’s position as a global network of Occupational Therapists (WFOT, n.d).

The RCM prototype will be developed under the supervision of RL’s Director, in consultation with a WFOT representative as SME. This partnership has already successfully delivered the currently available Working with Displaced Persons online course, which has received a LearnX award and wide recognition as an innovative e-learning program.

Design

The design for RCM is underpinned by learning theories such as connectivism and communities of practice, as well as Laurillard’s conversational framework (2002) and authentic assessment by Herrington (et al., 2009), with a predominant focus on the network of learners provided by WFOT, promoting articulation, reflection and collaborative construction of knowledge (Herrington et al, 2009, p. 18). The intention is to present issues around climate change migration, then ‘situate’ learners in the position of a climate migrant for meaningful learning to take place (Herrington et al., 2009, p.15), to facilitate ‘meta-cognitive’ awareness whereby learners use “productive habits of mind, developed through prior learning, to reflect on the meaning of current learning and experiences” (Steele, 2015). As such, RCM will feature interactive and multi-linear activities, steering users toward a self-directed pathway throughout the module.

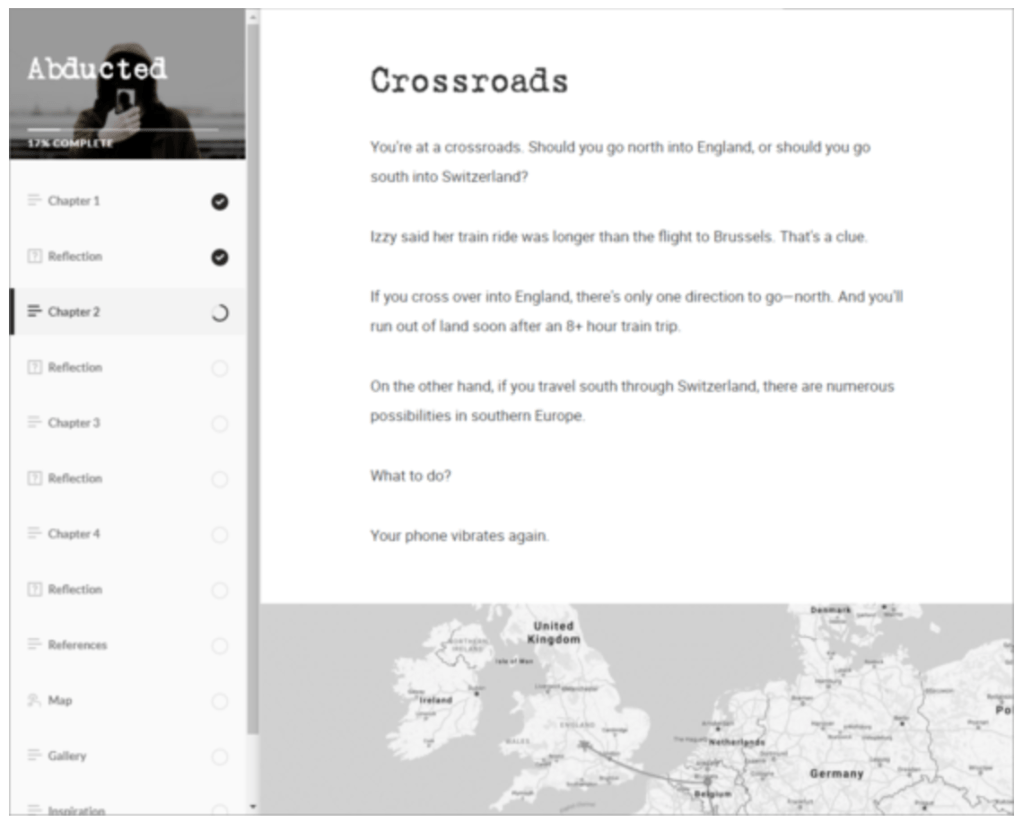

Most of the content will be authored in Articulate Rise 360, initially presenting 3 stories of people who have been displaced due to climate change. These will include a feature image with pop-up options linking to other resources for further information, similar to Figure 1. The popup text box helps preserve the layout, but using instructions like ‘click here’ should be avoided (E-Learn Australia, n.d).

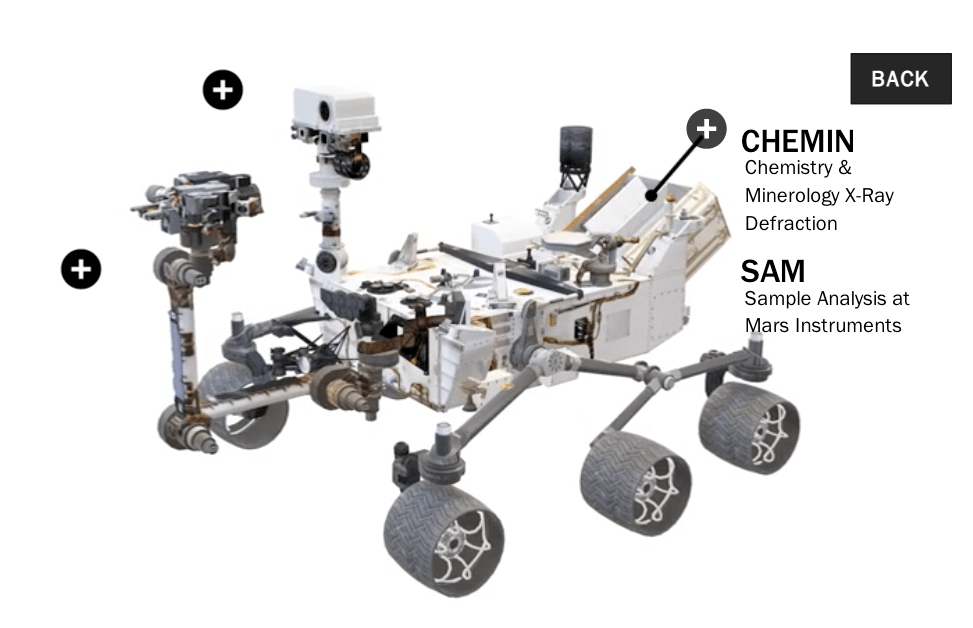

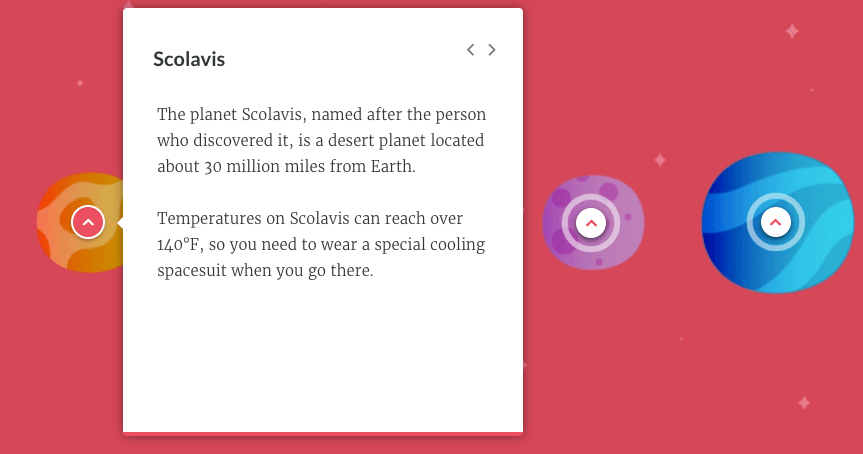

This style is used widely in Rise courses integrated with Storyline 360, such as Figure 2.1 in which a 3D model is annotated via a heads-up display, as well as Figure 2.2 which uses a caricatured approach (a useful option if an appropriate image isn’t available).

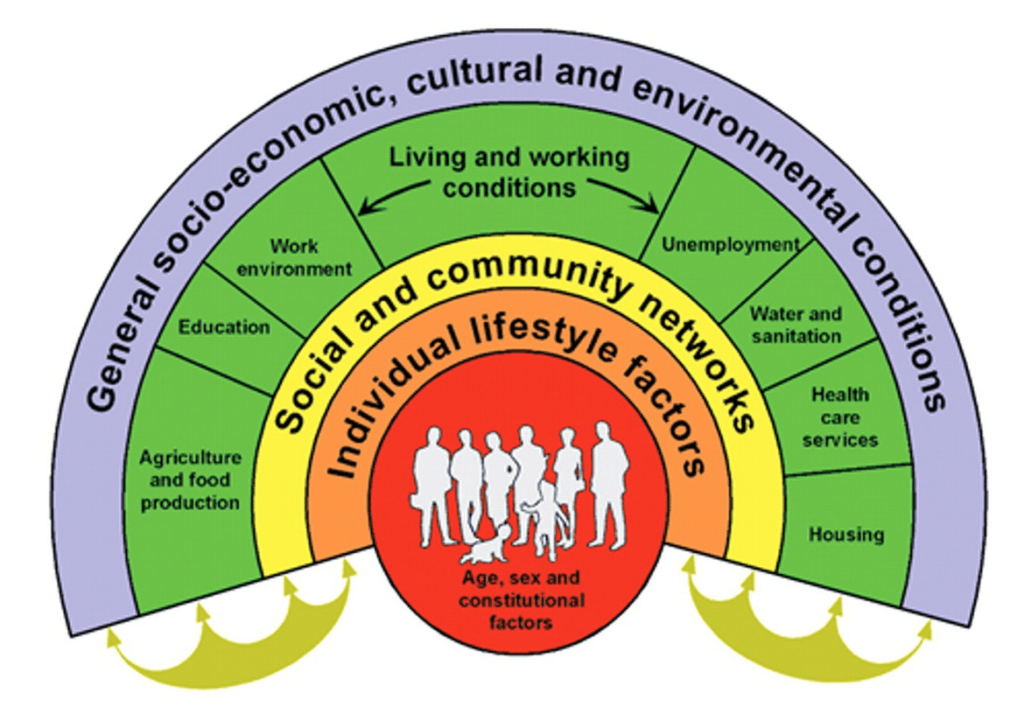

From here learners will be directed through a Rise Survey to create their own climate migrant identity (CMI). This survey will allow learners to make decisions about their CMI based on expertise or area of interest, the options for which will be derived from Figure 3 (Russell, 2016). Learners will select a country of origin, age, education level and more, then be prompted to conduct their own research into the broader conditions for their CMI as per the WHO guidelines.

The CMI activity will be largely fictional, but provides the “right kind of preliminary exercise” (Laurillard, 2002, p. 200) with the learner-centered principle of choice, which according to Weinberger & McCombs (2001) enables “a sense of ownership, empowerment, and enjoyment in their learning” (in Gonzalez-DeHass et al., 2012, p. 76). This sort of personalised learning also helps to facilitate self-regulation (O’Donnell et al., 2015, p. 30), thereby promoting inclusivity as it relies on the learners’ own experience and insights to construct new knowledge.

Once they have created a detailed profile of their CMI, learners will be prompted to develop criteria around their expectations for introducing their character to a new community, which will be revisited later in assessment. They will then be directed to ‘The Village’ Hub, a virtual space for situated learning to simulate the experience of their CMI arriving in a new community.

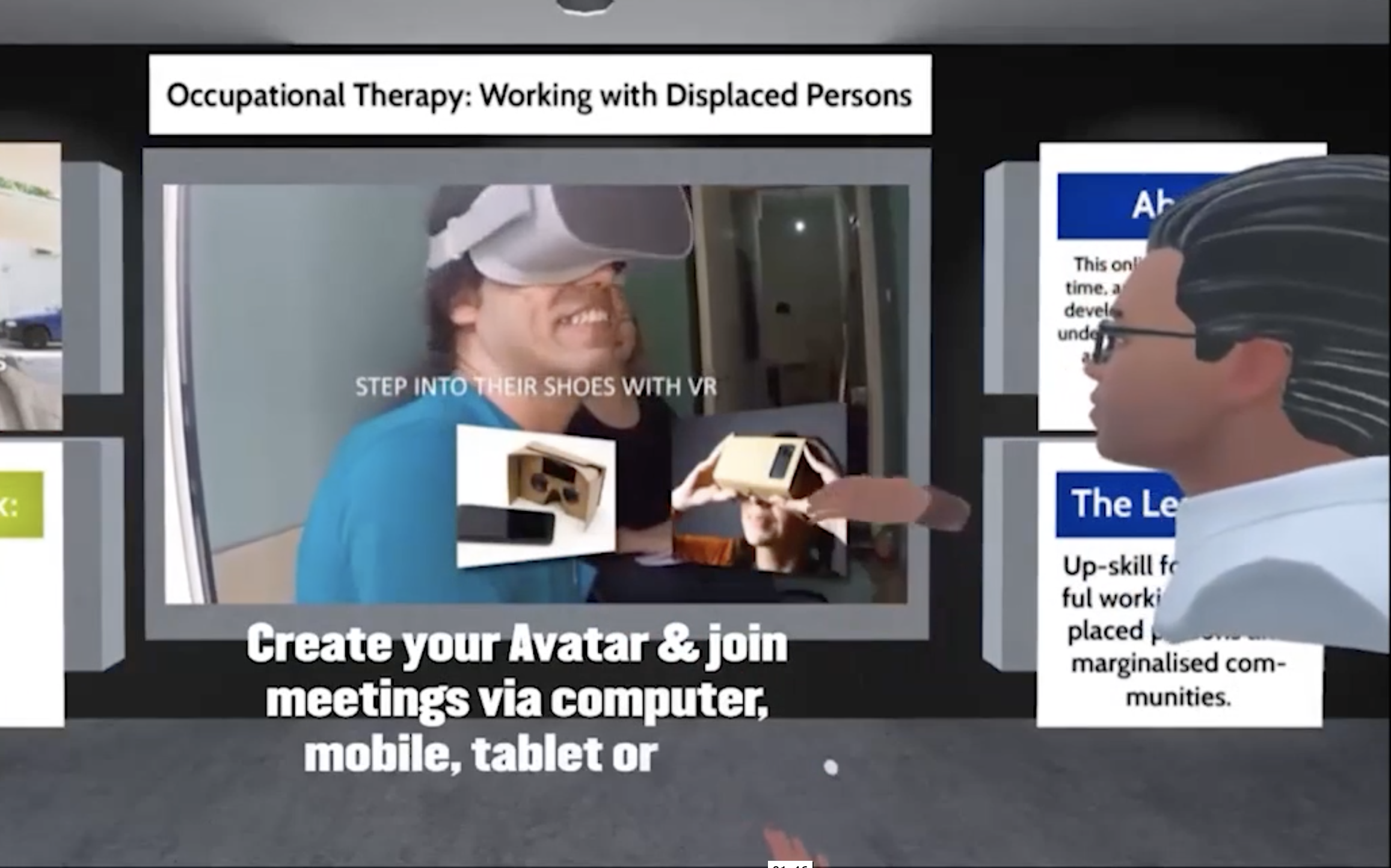

The hub will feature several ‘locations’ to check in, the list of which will be derived from Mary Pipher’s The Middle of Everywhere (2002), where learners will encounter relevant content though selected videos and web links. This ‘exploratoria’ model (Gomes de Siqueira et al., 2021) builds on the success of Hubs in WFOT’s Working with Displaced Persons course, allowing learners to move through the space and engage with a range of materials to direct their own learning (Figure 4).

‘The Village’ Hub lays the foundation for connectivism to evolve, as a platform that facilitates Laurillard’s key principals of learning through acquisition, inquiry, discussion, practice and collaboration (Eriksson, 2021, p. 3), where engagement is greatly enhanced (Gomes de Siqueira et al., 2021). Rather than learning facts and concepts, connectivism stresses learning how to create paths to knowledge when it is needed (Anderson, 2016, p. 43), where opportunities for leadership can emerge (p. 44) and ‘distributed scaffolding’ for learner needs amongst the network can take place (Couros et al., 2016, p. 146). Despite the benefits offered by Hubs, it does present some challenges with accessibility that will be addressed below. As such, a Moodle forum on WFOT’s LMS will further the ‘organisational forms’ to build learner relationships (Goodyear, 2005, p. 90), which will be discussed in the next section. The Hubs activity will culminate in learners developing a ‘welcome pack’ for their CMI based on the content that they encounter throughout the Hub, with further details on this still to be determined.

Assessment and Feedback

In keeping with the multi-linear and interactive nature of this module, assessment will focus on reflective practice and sharing knowledge within the network rather than seeking ‘correct’ answers. As learning is self-directed, this implies a need for self-assessment, which will be challenging without the presence of an instructor for feedback. However, aspects of Laurillard’s conversational framework will be adapted to these learning conditions in order to maximise outcomes for learners. While reflection and self-assessment are critical aspects of experiential learning, they are not necessarily enabled by mixed reality technology such as Hubs (Alexander et al., 2019, p. 25). Therefore, learners will be encouraged to articulate and explain their perspectives, engaging them in a dialogue to help develop their knowledge and frame questions (Laurillard, D. 2002, p. 186).

Formative Assessment

This will consist of knowledge checks throughout the module to shape appropriate types of questions as well as enable brief progress reflection (Gillies, 2020, p.105), which will be authored in the Rise 360 component of the module similarly to Figure 5.

Again, these will not be about selecting correct answers, rather they will provide feedback to learners on their choices as a means of scaffolding at critical times (Herrington et al, 2009, p. 18). This reflection ‘in action’ (Clements et al., 2011) will be provided at regular intervals throughout the module, as frequent self-evaluation is “highly efficacious in enhancing student achievement” (Boud, 2000, p. 157).

Summative Assessment

The summative assessment task will be somewhat more ambiguous than the formative, given that it will be so heavily reliant on self-directed learning and the engagement levels of the particular individual. It will require learners to examine the degree to which they have met criteria (Gillies, 2020, p.105), however it is important that the criteria be self-determined by the learner (Swan et al., 2006, p. 12). Therefore, assessment for the module will comprise multiple elements, all of which will be shaped by the learning outcomes:

- How thoroughly learners develop and research their CMI

- The expectations (criteria) they develop for successfully setting up their CMI in ‘The Village’

- The degree to which the welcome pack they develop meets their self-determined criteria

- Responding to a series of questions at the end of the module for reflection ‘on action’ (Clements et al., 2011)

This provides an overview of what the students will do, though perhaps the most important stage of assessment will be students posting their work and insights to the Moodle forum; sharing knowledge with the community of practice that enables them to learn with and from each other (Wenger, 2011, p. 4). While this presents a risk in that it relies entirely on the individual learner’s own motivation, this is characteristic of a community of practice whereby the ‘class’ (or in this case, the online activity) is not the primary learning event, rather the module is merely a space to act in “the service of the learning that happens in the world” (Wenger, 2011, p. 5). Self-direction and the ability to accomplish tasks independent of an instructor are common expectations of online learning (Dickenson et al., 2016, p. 154), and the real benefit of this module will be in learners utilising existing knowledge in an unfamiliar context, then sharing that with the community to create discussion and connection within the network.

Innovation and Technology

On one hand, a learning experience such as RCM might be seen as inherently innovative, with Pelleiter (et al.) suggesting that “microcredentials provide an innovative design pathway to keeping course offerings contemporary” (2021, p. 37). However, the innovation in this design will more so be a product of its dependance on learner creation and connection, which also presents a considerable risk around the quality of the experience for learners. To some extent, this module is technologically deterministic in that the platforms were selected prior to the development of learning outcomes and course material, which runs counter to the principals of backwards design (Wiggins et al., 1998) and constructive alignment (Meyers et al., 2009). However, the focus on interactivity, along with the immersion of Hubs and the elements of connectivism have been incorporated into the design mindful that technology “has to be for the education benefit of the student” (Pickering, 2015, p. 6). Again, the module is intended to be a space to prompt self and peer-directed knowledge construction within the WFOT network, rather than an attempt to impart facts to learners.

More specifically, the multi-linearity of the initial CMI activity using a Rise 360 survey is a simple way to create choice and enhance engagement for learners, as discussed earlier. Figure 6.1 demonstrates how Rise 360 features such as timeline, quiz, labeled graphic, and block lesson can be used to compel learning (Fair, n.d), and these will be used in the CMI activity as a way to customise an avatar and personalise the experience (Gomes de Siqueira et al., 2021), as seen in Figure 6.2.

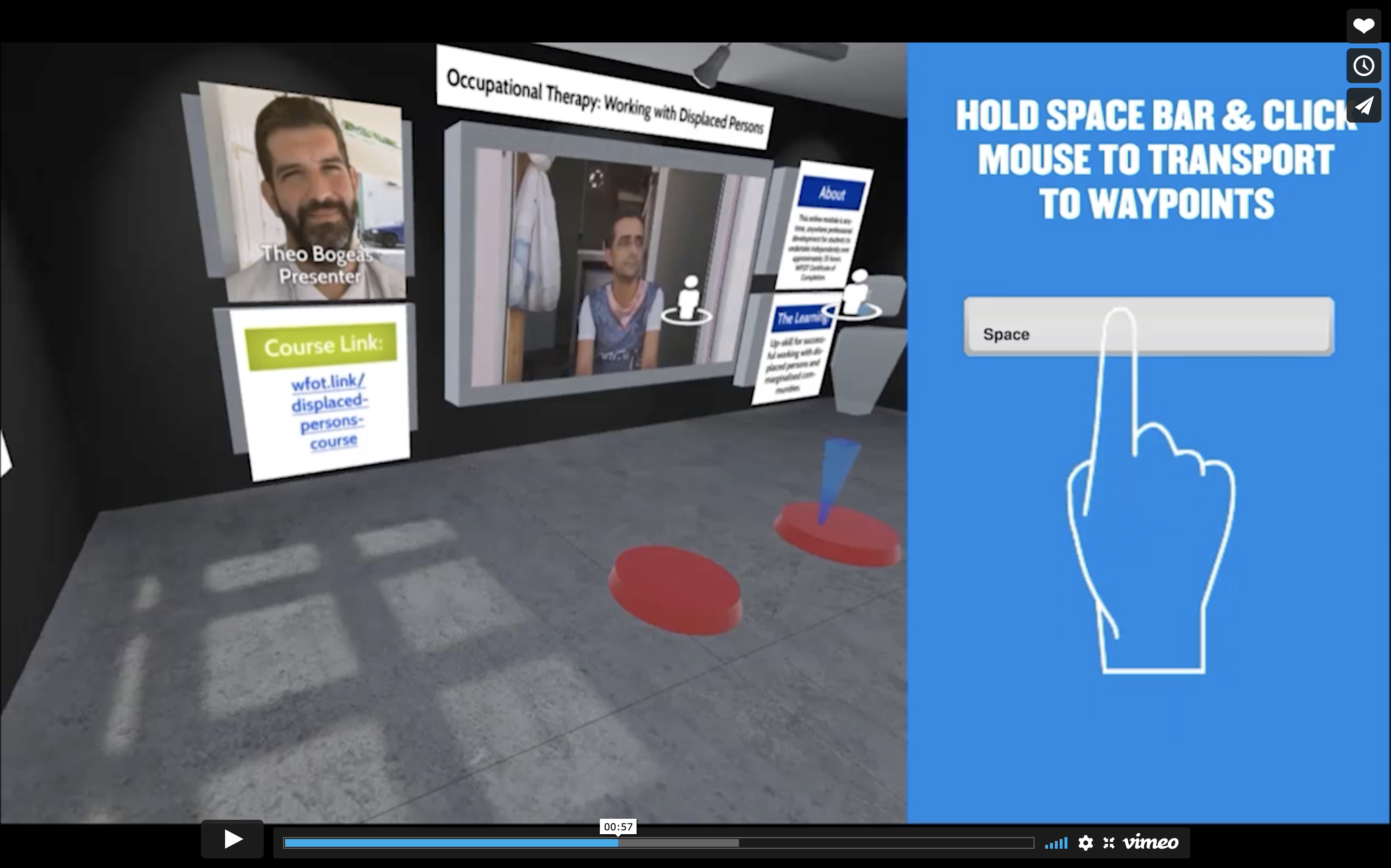

The use of Hubs is the most innovative aspect of this module, allowing for high level engagement in the content (Gomes de Siqueira, 2021), with limited technical barriers as it can be accessed from an up-to-date browser with only a few clicks. Basic navigation is simple using the mouse to look and interact (such as play a video) and the direction keys on the keyboard to move, and these controls are modelled similarly on mobile device. Most importantly Hubs can be accessed through a VR headset, offering even greater immersion for learners “as if they were really experiencing it” (Herrington et al., 2009, p. 88). This interface will require some technical instruction as per Figure 7, and so therefore will not be ‘operationally transparent’ (Laurillard, D. 2002, p. 193), however the immersive nature of Hubs will allow for suspension of disbelief which also encourages self-direction and independent learning (Herrington et al., 2009, p. 95).

There are two key factors that have yet to be addressed, namely accessibility and learning analytics. Authoring in Rise will contend with some of the assistive and adaptive elements required for WACG compliance (E-Learn Australia, n.d), along with a design that involves simple interfaces and text alternatives for audio conversion. Hubs presents greater challenges, and as such there will be others ways to access content made available including a list of resources and text alternatives. Adding to this, designing a module for a potentially global audience in English will require options for other languages, and videos will be embedded from Youtube or another platform which allows closed caption translation. Aside from the challenges in equitable access, the learning activities rely heavily on personal experience and therefore allow for inclusivity, having been developed from the outset “with universal design in mind” (Bozarth, n.d.).

Limited learning analytics will be available. such as those provided by Moodle which tend only to be descriptive in nature (Moodle, n.d). The module will not be administered or overseen in any way, and likely not evaluated for future improvement, which again limits the role that analytics might commonly play (Gašević et al., 2016, p. 83). As for course content, Rise will provide data on student completion and quiz scores, Hubs doesn’t capture any records of user activity, while the Moodle forum will be a space for ad-hoc feedback or suggested improvements. Again however, there may not be resources available to act upon these. One idea is to use any available data from the existing Working With Displaced Persons offering, which can suggest “key risk variables given their instructional aims, specific student tool-use requirements and (where available) the outcomes of previous student cohorts” (Gašević et al., 2016, p. 83). Information such as learner commencement, completion, geographical region and any professional details would help to shape a profile of demographics and engagement levels, giving insight into the idiosyncrasies of the Occupational Therapy profession for the design of appropriate learning materials.

References

Alexander, B., Ashford-Rowe, K., Barajas-Murphy, N., Dobbin, G., Knott, J., McCormack, M., Pomerantz, J., Seilhamer, R., Weber, N. (2019). EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: 2019 Higher Education Edition. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE.

Anderson, T. (2016). Theories for Learning with Emerging Technologies. Emergence and Innovation in Digital Learning: Foundations and applications. (Veletsianos, Ed.). ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Articulate. (2020). Quizmaker ’13: Editing the Result Slide. Web Page. Retrieved on 8th November 2021 from: https://articulate.com/support/article/Quizmaker-13-Editing-the-Result-Slide

Articulate. (n.d). Futuro Spaceship Attendant Training 101. Online Course. Retrieved on 8th November 2021 from: https://rise.articulate.com/share/PiXseUL0nmncLNK33l-L7kTWnfUg_xfb#/lessons/vM1woDleftX84Zp0NrXhHWf77hQMeNZL?_k=b69rhr

Articulate. (n.d). Training Needs Analysis 101. Online Course. Retrieved on 8th November 2021 from: http://articulate-heroes-authoring.s3.amazonaws.com/Nicole/Demos/Rise/training-needs-analysis/content/index.html#/lessons/64Gj6_ZTMZiyoT6t33liVJEi5kUqQp1D?_k=3q8m4w

Boud, D. (2000) Sustainable Assessment: Rethinking Assessment for the Learning Society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22:2, pp 151-167, DOI: 10.1080/713695728

Bozarth, J. (n.d.) “But it’s to code”: Thoughts on Accessibility in E-Learning. Web Page. E-Learning Heroes, Articulate 360. Retrieved on 1st November 2021 from: https://community.articulate.com/articles/but-it-s-to-code-thoughts-on-accessibility-in-e-learning

Clements, M. & Cord, B. (2013). Assessment Guiding Learning: Developing Graduate Qualities in an Experiential Learning Programme. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(1), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.609314

Couros, A., Hidebrandt, K. (2016) Designing for Open and Social Learning. Emergence and innovation in digital learning: Foundations and applications. (Veletsianos, Ed.). ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Dickenson, P., & Jaurez, J. J. (Eds.). (2016). Increasing Productivity and Efficiency in Online Teaching. IGI Global.

E-Learn Australia (n.d.) How to Make Your E-Learning Accessible. Web Page. Retrieved on 8th November 2021 from: https://www.elearnaustralia.com.au/howto_accessibility.htm

Eriksson, T. (2021). Failure and Success in Using Mozilla Hubs for Online Teaching in a Movie Production Course. 2021 7th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.23919/iLRN52045.2021.9459321

Fair, D. (n.d). Rise: Abducted Adventure Game. E-Learning Heroes. Web Page. Retrieved on 3rd November 2021 fropm: https://community.articulate.com/e-learning-examples/rise-abducted-adventure-game

Gašević, D., Dawson, S., Rogers, T., Gasevic, D. (2016). Learning Analytics Should Not Promote One Size Fits All: The effects of instructional conditions in predicting academic success. The Internet and Higher Education. Volume 28. Pages 68-84. ISSN 1096-7516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.10.002.

Gillies, R. (2020). Inquiry-based Science Education. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429299179

Gomes de Siqueira, A., Feijóo-García, P., Stuart, J., Lok, B. (2021). Toward Facilitating Team Formation and Communication Through Avatar Based Interaction in Desktop-Based Immersive Virtual Environments. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2021.647801

Gonzalez-DeHass, A., Willems, P., (2012). Theories in Educational Psychology : Concise Guide to Meaning and Practice. R&L Education. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=1127723.

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational Design and Networked Learning: Patterns, Pattern Languages and Design Practice. Australiasian Journal of Educational Technology. 21(1). Pp. 82-101.

Henley, J. (2020). Climate crisis could displace 1.2bn people by 2050, report warns. The Guardian, 9th September 2020. Retrieved on 21 October 2021 from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/09/climate-crisis-could-displace-12bn-people-by-2050-report-warns

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. C., & Oliver, R. (2009). A Guide to Authentic E-Learning. Routledge.

Kuhlmann, T. (n.d). Mars Curiosity Rover (Orig). Online Course. Retrieved on 8th November 2021 from: https://rise.articulate.com/share/uxzFpO1QkrS5RugqYn6rRtd_MKaYlggI#/

LaMotte, A. (n.d). Rise 360 or Storyline 360: Which One Should You Use for Your Project? E-Learning Heroes. Web Page. Retrieved on 3rd November from: https://community.articulate.com/articles/rise-or-storyline-which-one-should-you-use-for-your-project

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi-org.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/10.4324/9781315012940

Meyers, N. M., & Nulty, D. D. (2009). How to Use (five) Curriculum Design Principles to Align Authentic Learning Environments, Assessment, Students’ Approaches to Thinking and Learning Outcomes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(5), 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930802226502

Moodle. (n.d). Analytics. Web page. Retrieved on 3rd November from: https://docs.moodle.org/311/en/Analytics

O’Donnell, E., Lawless, S., Sharp, M., & Wade, V. P. (2015). A Review of Personalised E-Learning: Towards Supporting Learner Diversity. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies (IJDET), 13(1), 22-47. http://doi.org.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/10.4018/ijdet.2015010102

Pelletier, K., Brown, M., Brooks, D. C., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., Arbino, N. (2021). 2021 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report, Teaching and Learning Edition. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE.

Pickering, J. (2015) How to Use Technology in Your Teaching. Highter Education Academy. Retrieved on 3rd November 2021 from: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/how-start-using-technology-your-teaching

Pipher, M. (2002) The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Second Edition.

Reality Learning. (2021). Welcome: WFOT 3D Education Hub. Video. Retrieved on 8th November from: http://realitylearning.org/new-3d-education-rooms-launched-in-prague/

Russell, L. (2016). NACCHO Aboriginal Health #SDoH News: Delivering better health is about more than healthcare. Blog Post. Retrieved on 3rd November 2021 from: https://nacchocommunique.com/2016/08/18/naccho-aboriginal-health-sdoh-news-delivering-better-health-is-about-more-than-healthcare/

Shopmart. (n.d). Customer Service Training: How to Process A Return. Online Course. Retrieved on 8th November 2021 from: http://articulate-heroes-authoring.s3.amazonaws.com/Nicole/Demos/Scenario-ProcessAReturn/output/story_html5.html

Steele, G. (2015). Using Technology for Intentional Student Evaluation and Program Assessment. Nacada. Web page. Retrieved on 3rd November 2021 from: https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Using-Technology-for-Evaluation-and-Assessment.aspx

Swan, K. Shen, J. & Hiltz, R. (2006). Assessment and Collaboration in Online Learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 10 (1). Pg. 45-62.

Wenger, E. (2011) Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. STEP Leadership Workshop, University of Oregon. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1794/11736 22 February 2021.

WFOT (n.d). Welcome To The World Federation Of Occupational Therapists. Retrieved on 21 October 2021 from: https://www.wfot.org/

Wiggins, G., McTighe, J. (1998). Chapter 1: What is Backwards Design? Understanding By Design. ASCD. Retrieved on 4th November from: https://educationaltechnology.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/backward-design.pdf

Leave a comment